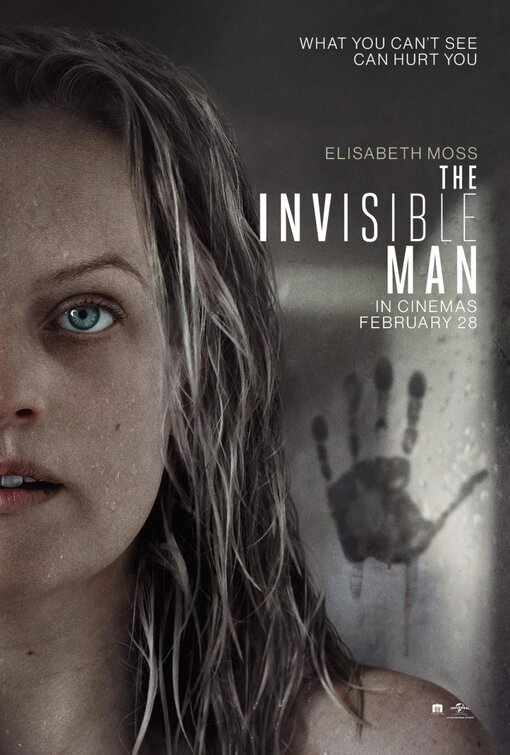

What You Can’t See Can Hurt You

Director

Leigh Whannell

Starring

Elizabeth Moss

Oliver Jackson-Cohen

Opening with Cecilia [Moss] escaping the clutches of her abusive boyfriend Adrian [Jackson-Cohen], we watch her rehabilitate while in hiding. This is until she learns that Adrian has committed suicide and left his money to her. Finally free, Cecilia tries to move on with her life but is tormented by a series of circumstances that lead her to believe that Adrian has somehow faked his own death to torment her. This fear escalates and Cecilia’s few allies are slowly pushed away, leaving her isolated and without anyone to trust.

After what feels like two decades trying to jump-start a resurrection of the iconic Universal monsters – the most recent failure being the commercially and critically lambasted The Mummy – Universal went back to the drawing board and created a contained, modern adaptation of H.G. Wells’ novel. To my mind, the last big invisible man release was 2000’s Hollow Man which ended up being little more than a male fantasy piece portrayed as scandalous indulgence. The unique aspect to this version is the emphasis on the monstrousness of Griffin and shifting the perspective from the killer to his primary target, while ultimately presenting an allegory for domestic abuse. And as such the final result feels fresh, poignant and remarkably tense.

The first thing that stands out about this film is how fantastically it has been constructed. From the extremely unnerving but simply opening scene, the location is beautifully shot but this escalates following Griffin’s death and the camera takes on a terrifying quality by framing certain shots to include empty spaces as if someone else was stood in the scene, going so far as to include a few tracking pans and focus pulls. This is heightened by pivoting from the uneasy opening to disarming family bonding before finally giving way to voyeuristic camera angles and a creeping sense of disquiet and growing apprehension. Catching the audience off-guard with banal relatability (situations that lull you with their familiarity before disrupting them with a horrific act) is far from a new technique, but here it is a keenly utilised weapon from the horror/psychological thriller arsenal.

Owing to the nature of not being able to see the danger, a lot of this tension comes down to aural manipulation; much like A Quiet Place, this film has come seemingly out of nowhere and is heavily reliant on what you can hear more than what you can see. Benjamin Wallfisch has proven himself multiple times over with a range of diverse and varied orchestral scores and while horror can be very formulaic in its musical output, the accompanying score has a fantastic presence, building masterfully from painfully ominous to thunderous and terrifying. The real unsung hero of this film is the sound design and mixing which go beyond the standard foley work, creating a whole character from nothing. After absorbing a medium like film for so long, we begin to accept the established rules, the pact that when a character moves across a room, you will hear a combination of audio recorded on the day and manufactured ambience to enhance the immersive experience. But to put these markers in place without a visual counterpart leaves the audience unnerved. I will, of course, admit that this isn’t some revolutionary new practice, it’s how every single feature with an unseen villain has operated for the best part of ninety years but it’s done extremely well and that’s what stands out.

**light spoilers concerning the nature of invisibility**

No matter the cause for the titular character, whether it’s technology, science or the supernatural, eventually CGI will need to play a role. And for the most part, it’s fairly absent and pleasingly subtle. For a large portion of the runtime we aren’t given definitive evidence that Cecilia is experiencing an actual attack and as such when her fears are confirmed, the audience begins to question how this is possible. Rather than the tried-and-tested method of a chemical compound – as used in previous iterations of the adaptation – this version opts for a technological morph-suit covered in cameras. It’s one of those novel changes that feels close enough to be a possibility while still firmly in the realm of science fiction. A wonderful by-product of this is the gentle whirring of the lenses as they shift focus, creating an eerie signature to torment the audience with later.

One of the reasons I genuinely love this movie is the character shift. From the opening scenes, the movie makes the smart choice of keeping Adrian largely in the shadows, never giving us a clear look at anything more than a very masculine form. This is magnificently used later to not only make the threat more foreboding but also to crushingly illustrate the nature and effect of abuse; just the idea of the silhouette is enough to terrify both Cecilia and the audience. Without getting too far into spoiler territory, the film progresses decently with its premise (arguably with a few conveniences for the sake of prolonging the suspense) but due to the perfect execution of a terrifying twist that invalidates Cecilia and the control dynamic shifting repeatedly over the three acts, The Invisible Man proves itself an absolutely worthy successor and/or companion piece to the 1933 original.

Release Date:

28 February 2020

The Scene To Look Out For:

**spoilers**

With absolutely no pun-work intended, you don’t see a lot of the invisible man. The encounters are fairly limited to avoid weakening the impact but when he is finally on-screen, the experience never disappoints. One could argue the most memorable section, when Adrian finally drops the veneer of manipulator and marches confidently into unhinged serial killer, takes place in the asylum corridor. Cecilia has managed to get out of her cell by wounding Adrian, causing his suit to glitch but using this to his advantage he proceeds to brutally attack the facility guards. While there are several examples of gripping filmmaking, this scene demonstrates the flow of action and brilliantly executed choreography that we saw in Whannell’s last film, the stupidly underrated Upgrade.

Notable Characters:

Elizabeth Moss has proved herself time and again as a go to for extremely relatable performances, from more comedic turns in something like The Square to dark dystopian pieces like The Handmaid’s Tale, she is always captivating. Keeping the narrative focus on Cecilia creates a very different feature with a unique dynamic and there is so much pressure on that individual to keep the audience both hooked and convinced by the absurdity of what is taking place.

Highlighted Quote:

“Adrian will haunt you if you let him. Don’t let him”

In A Few Words:

“An absolutely fantastic and unsettling release that morphs and evolves from beginning to end”

Total Score: 5/5

![The Red Right Hand Movie Reviews [Matthew Stogdon]](https://reviews.theredrighthand.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/cropped-header1.png)