Director

Hayao Miyazaki

Starring

Soma Santoki

Masaki Suda

Aimyon

Ko Shibasaki

Takuya Kimura

Shohei Hino

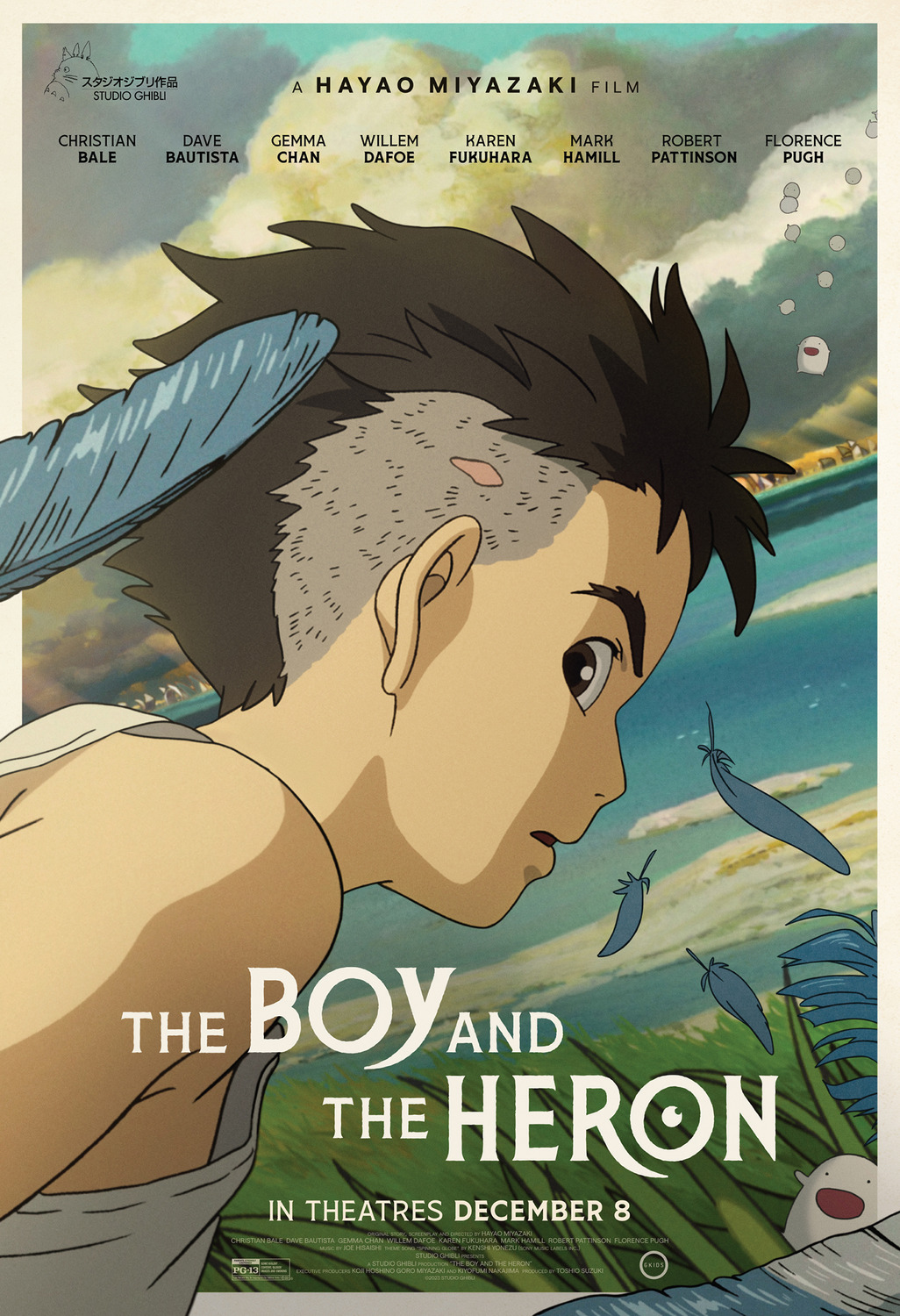

After his mother dies in a fire, twelve year old Mahito [Santoki] is evacuated to the countryside. There, his father continues his work building munitions for the war effort. But the entirety of the second world war is fairly distant for Mahito. His primary concern is not fitting in at school, feeling uneasy in his new countryside estate, and an unwillingness to connect with his new, pregnant step-mother. As the weeks go by, Mahito grieves the loss of his mother, explores the grounds, and is seemingly harassed by a mysterious grey heron, before descending into another realm.

Despite being a decade since the last one, many viewers will know that a Miyazaki-helmed Ghibli film comes with a certain set of guarantees – namely luxurious visuals, complicated but relatable characters and glorious adventure. Thankfully, The Boy And The Heron is no different. Every frame is painstakingly detailed and brought to life with exquisite, iconic motion, and complemented by Joe Hisaishi’s piano-led score, rich with a simple sense of power and wonder.

It must be said, however, that for those expecting a charming innocent tale, this film skews closer to the darker elements of something like Princess Mononoke. Because while there are cuddly creations like the orb-like warawara, every soft aspect has a hard edge undercutting it. Even the dreamlike transitions, which feature prominently throughout, are presented with a smothering, overwhelming dread. In essence, with Mahito being so consumed by his grief, guilt and depression, he finds himself continually swarmed by animals and the elements. While these were likely not direct influences, there are a lot of interesting parallels with films with European fairytale origins such as A Monster Calls, Pan’s Labyrinth and, of course, The Wizard Of Oz. Creating a very personal tale of death and birth, legacy, and souls passing between both worlds.

On the whole, the performances are exactly what we have come to expect: a mix of voice acting talent at the top of their game, and celebrity inclusions such as Kimura and Aimyon fitting in magnificently. And, whether voiced or not, so many of the characters are beautifully memorable. There’s the mischievous and unknowable Heron, stalwart Mahito, and even silent characters such as the army of parakeets hungry for human flesh. But, despite how well each is presented, there is a touch of confusion every now and then. Let’s take Kiriko [Shibasaki] for example. When Mahito moves to the countryside he is attended by several wonderfully crafted old maids. One in particular is Kiriko, who follows Mahito into the other world. There, however, she is a much younger woman who has seemingly always lived there. What’s unusual is that, during the introduction, Kiriko isn’t highlighted as more important than the others, and while she clearly understands this subterranean world, it’s never explained how. As such, the film can’t decide if she’s integral or incidental.

And while we’re pulling threads and analysing flaws, let’s talk about the movie’s pacing – easily its weakest element. On the one hand, I will absolutely defend the way scenes linger and hang. Each pregnant pause is deliberate and shows how unafraid Miyazaki is to tell this story patiently. However, while each stage of the adventure is beautifully constructed, the narrative as a whole never seems to get to the heights we’ve come to expect. Part of this may come from the fact that nearly half of the runtime slips by before we fully transition to the other world. Which feels surprisingly long for a Ghibli fantasy. But that can be forgiven if the pacing for the second half unfolds effectively. But it rushes from pillar to post, before slapping viewers with a very abrupt close – and I do mean ‘slapping,’ as every audience member will feel sucker-punched when the credits suddenly roll. It’s far from amateurish and the film does conclude appropriately, it just doesn’t give the audience time to deal with the emotional and symbolic conclusions presented. To put it more bluntly, this is one of those rare Ghibli films that you’ll feel like you want to cry at the end of, but the film doesn’t permit it; leaving you somewhat unfulfilled.

These frustrations aside, there’s a rarely seen old world quality to this movie. One which is rigidly set in the 80s. Now, don’t get me wrong, that’s meant less as an indictment of Miyazaki’s work (after all, it’s not nostalgia bait) but more as a reminder that artists can stay loyal to their visions without compromise. And while Studio Ponoc, Makoto Shinkai, Mamoru Hosoda and other contemporaries are pushing the envelope, Miyazaki is happy to carve out another slice of a distinctly iconic and welcome style, that we will all thoroughly miss when it’s gone.

Release Date:

26 December 2023

The Scene To Look Out For:

The movie opens with the death of Mahito’s mother and, for all the fantastical sights, this grounded scene is one of the most impactful. Capturing not only the warped effect of rising heat and rushing bodies, but the evocative emotions coursing through Mahito as he desperately rushes to his mother’s side. While not on the same level (although few things may ever be) it feels very reminiscent of Kaguya escaping the palace and running into the forest in The Tale Of The Princess Kaguya. A primal example of emotive impressionistic visuals over realism.

Notable Characters:

Long term Ghibli fans will know that many of Miyazaki’s protagonists are drawn from his own life and experiences but, to date, these have been fairly subtle inclusions. However, as a boy whose father worked for a plane manufacturing company during World War II and was evacuated to the countryside as a child, the parallels are most pronounced here. That said, the most interesting Miyazaki substitute is in fact the granduncle. An exceptional man buried in his work, who one day disappears from this world. Only for him to be found as an ageing figure, desperately hoping for a successor to keep his world alive but unable to find one. Arguably arrogant, but potentially justified.

Highlighted Quote:

“Look at them. None are real. In this world the dead are the majority.”

In A Few Words:

“While it may not be the final masterwork fans will expect, The Boy And The Heron is another welcome arrow in Miyazaki’s already impressive quiver.”

Total Score: 4/5

![The Red Right Hand Movie Reviews [Matthew Stogdon]](https://reviews.theredrighthand.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/cropped-header1.png)