Director

Kenneth Branagh

Starring

Jude Hill

Caitríona Balfe

Jamie Dornan

Judi Dench

Ciarán Hinds

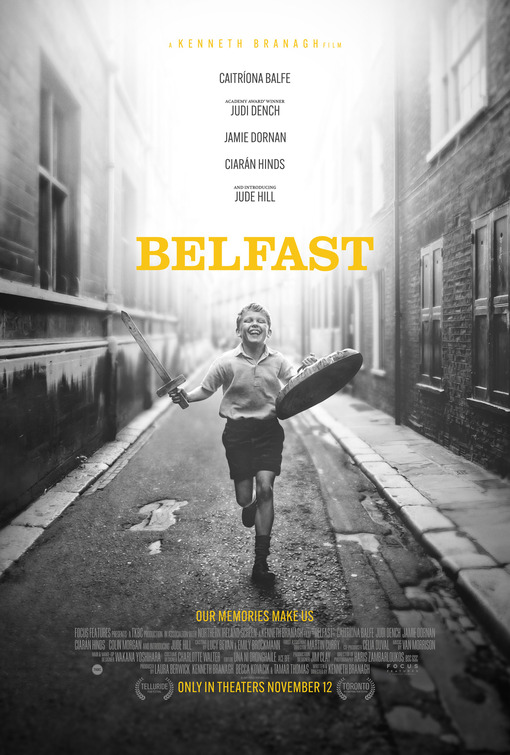

Set during the height of the Troubles in Northern Ireland in the late 60s, we are introduced to nine year old Buddy [Hill]. The young boy’s world is one of barricades, checkpoints and violence at odds with the innocence of trying to get ahead in school and being true to his family. As such, equal weight and runtime is given to the boy’s everyday life struggles as well as his parent’s conflict about whether it’s safe to stay in Belfast.

From the outset, it’s clear that this film is a fantastic visual treat. The cinematography is beautiful, the framing – with its deep, layered tableaus – is engrossing and, combined with the immaculate production design, feels like the footage has been plucked from the past. Following the initial vibrant introduction to a prosperous city at peace in the 2020s, we make two smooth transitions. The first is into black and white as August of 1969 is a bustle of life and jollity with neighbours socialising and kids playing in the back alleys. This is quickly turned on its head as a group of Protestants firebomb the street, intimidating the Catholic residents and shaming the others on the road for their association. The only break of colour we are treated to, is Buddy’s escape through art, specifically the cinema and theatre offering the only the escape from a grey turbulent world.

Many viewers may not realise that when you remove colour from the screen it brings the human component into stark contrast – specifically the faces. And at its core, Belfast has some truly tremendous performances. Hinds and Dench are charming as Buddy’s grandparents and there’s a splendid complexity to Dornan and Balfe as Buddy’s parents; with the majority of the drama peripherally observed rather than fully explored. And of course at the centre of all this is the confident and tenacious presence of Jude Hill, who shines from the word go.

Overall, the story being told is one of tenderness wrapped in unease; as if a jumble of memories remembered hazily. Which is probably no coincidence as the general setting and events mirror Branagh’s own upbringing. What sets Belfast apart from many other films set during the Troubles is the current of sly humour coursing throughout; the clearest examples focusing on religion and family. Getting in trouble for stealing from a newsagents then running up the stairs to avoid a hiding, being unable to quantify what makes Catholics and Protestants different other than minutiae like confession and working hard in school to sit next to the girl he likes only to learn she has been moved because she is trying to do the same thing – all of these are all incredibly relatable little vignettes of childhood in a certain time. But all the while, Buddy can see the strain his parents are under, even if he can’t really process why.

But that positive aspect is a double-edged sword. This world we’re introduced to is only ever explored through the eyes of this nine year old boy; to the extent that many of the central characters are only ever credited as Ma, Pa, Granny and Pop. But by retaining this earnest recollection, we are only offered glimpses of the bigger picture. And while Belfast does a great job of presenting the adolescent point of view of turbulent times told whimsically through the eyes of a child, it struggles to marry the two. If you take something like Derry Girls or Jojo Rabbit, both do a great job of ramrodding how disruptive reality is for the central characters. And every time it catches you off guard. But for something like the Troubles, by never fully covering a lot of the horrors outside of allusion, Belfast finds itself surprisingly toothless. With that in mind, it could easily serve as a simple introduction to the story you may not know and a gateway to heavier pieces.

This minor gripe aside and despite wrestling with disparate tones of cynicism and fear, positivity and hope, Belfast manages to present an engaging impression of a period of instability, all the while conscious of how easy it would be to return to. And as a simple story with a strong personal connection, it is easily Branagh’s best film in decades.

Release Date:

21 January 2022

The Scene To Look Out For:

As the film is essentially a series of vignettes, there are several moments I could highlight. One that both drew me in and frustrated me was an exchange between Ma and Pa. Dornan’s character is set to return to England for work but has been offered the opportunity to move there permanently. Balfe’s character understands this would likely be positive for her sons’ future prospects but addresses the inherent fear of leaving Belfast for the risk of persecution and the unfamiliar: no family, no friends, no connections and the constant presence of others who would hate and fear them, blaming them for the death of “their boys” serving in the north and taking a home that could go to an English family. It’s a simple crushingly blunt relatability that immediately speaks to any generation of immigrants.

Notable Characters:

Much like the previous paragraph, there are several strong components but Colin Morgan plays what we could identify as the film’s antagonist. Centuries of English occupation and interfaith violence isn’t fully covered so instead we get an angry and violent young man trying to recruit everyone to the cause – that being Ulster loyalism. The performance is solid and his presence is felt but we’re never clearly shown how and why he’s a threat outside of a few punches and taunts. Again, it’s that trouble of trying to play the film fairly safely without directly offending anyone, to the film’s detriment.

Highlighted Quote:

“I wouldn’t worry about it, the Irish were born for leaving, otherwise the rest of the world would have no pubs. It just needs half of us to stay so that the other half can get sentimental about the ones that went”

In A Few Words:

“An intimate portrayal of a tempestuous era that ends up grappling with its chosen tone”

Total Score: 4/5

![The Red Right Hand Movie Reviews [Matthew Stogdon]](https://reviews.theredrighthand.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/cropped-header1.png)