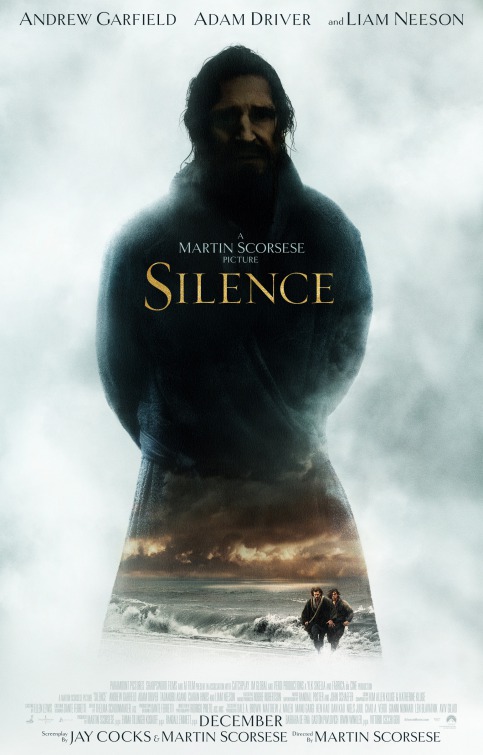

Sometimes Silence Is The Deadliest Sound

Director

Martin Scorsese

Starring

Andrew Garfield

Adam Driver

Yosuke Kubozuka

Issei Ogata

Tadanobu Asano

Liam Neeson

In the early 1600s the nation of Japan effectively closed its borders and outlawed foreign influence. One of the most devastating effects of this decision was the execution of those who had converted to Christianity. The Jesuit priests and missionaries who took the island as their home were tortured and ordered to recant their faith. Word reaches Portugal of one such priest, Father Ferreira [Neeson], who has openly apostasised and taken up the life of a Japanese native. Two of his young students, Fathers Rodrigues [Garfield] and Garrpe [Driver] believe this to be little more than scandalous slander and request permission to travel to Japan and uncover the truth. Doing so will put their lives at risk but they believe their faith will see them through. The priests make their way to Japan with an alcohol-sodden despot named Kichijiro [Kubozuka] and find a series of townships practicing their religion in secret. The longer the men stay in Japan, the greater the risk of their discovery and as those around them are interrogated and persecuted, both men begin to question the value and validity of their cause.

Silence is an incredibly thought provoking film from a director who has been tussling with his own doubts, concerns, fears and faith for his entire cinematic career. With such a melting pot of ideas about religion, xenophobia, foreign invasion, finding ones mentor and enduring gruesome horrors, this movie feels very reminiscent of Shogun, The New World, The Mission and Apocalypse Now. To break down the plot to its barest of elements reveals it’s less a story and more an assessment of stubbornness and faith, and the merits and detriments of both. I always maintain that cinema is an experience first and entertainment second, as such I feel this is not a film to be loved or loathed, it’s one to be experienced and poured over. Naturally, that’s not exactly the most popular theory so a lot of cinemagoers will find this film to be slow, tedious and extremely long.

At the heart of this film is an array of great performances. The characters themselves are incredibly complex despite their simplicity, divided between the faithful and those who want to stamp it out. As with the majority of Scorsese’s releases, this film is dominated by a central individual with whom we experience the story and Garfield fills the role with a wealth of energy and fervour. The supporting cast give some truly wonderful performances from the charming and deceptively upbeat inquisitor, Inoue Masashige [Ogata], to the mercurial and layered guide Kichijiro and the polite but pragmatically cruel interpreter [Asano]; not to mention the various devotees who live in constant fear of their allegiances being discovered. The only improvement I could see would be to switch Driver with Garfield. Adam Driver did a marvellous job as Rodrigues’ colleague, Garrpe, giving us a portrayal of fear, anxiety, doubt, frustration, courage and despair. That’s not to say these qualities weren’t present in Garfield or that he did a poor job, I just feel the actors would have been better suited to the other’s respective character.

As with most period dramas, the production value is superb. From the costumes to the sets, to the hair and make-up, everything lives and breathes with an air of authenticity. Equally, the cinematography is stunning, offering an initially stark and cold look at this mysterious distant island before slowly giving way to intense daylight and gruelling heat as Rodrigues’ time in Japan progresses. It may not sound like much but ensuring a film maintains a uniform look and feel with such dramatic changes in weather and lighting is far from easy. One key thing to highlight is a notably interesting use of editing. Scorsese has never been one to care about continuity, to the extreme that people entering through a door will often switch places between cuts, but more-so than that the jumps between developments are sometimes jarring but in an almost justifiable way. Whereas we would immediately slate this action as incompetence or negligence, here it’s merely a reflection and extension on the nature of torture and endurance (both of which play a huge part in this movie) manifesting disorientation and lost time. Ultimately, as the inquisitor has orders to eradicate Christianity from Japan a simple execution is denied Rodrigues and suddenly the clean martyr’s death that he may have expected is replaced with the suffering of others in his name; which gives way to such a poignant conversation about pride, guilt, arrogance and the lengths people will go to in order to preserve their way of life.

I will acknowledge this film is far from perfect. Much in the same way The Revenant was a fantastic release but left a lot to be desired, Silence commits its own acts of arrogance, some of which stem from the source material. First of all, a lot of people are going to find this film excessively long. Granted, the two and a half hour runtime isn’t uncommonly protracted but the crawling, meticulous pacing will take some audience members by surprise. In truth, I think the story really does need all 161 minutes, if only to draw out Rodrigues’ suffering and illustrate how much he has to endure to justify the film’s epilogue. Regrettably, one of the most important factors in any release, the music, is wanting. There were only a handful of occasions that I became aware of the background score and even when I was, it felt largely ambient. For me, with such a laboured unfolding of plot, a strong musical presence would have really elevated everything. Finally, we have to talk about the notion of the book itself. The novel, Silence, was written by Shusaku Endo, a Japanese Catholic dealing with his own religious turmoil and discriminations, and yet there is still the potential for this story to come off as very one-sided. It’s clearly documented how Japan treated foreigners during Sakoku but with the only spokesmen being the wellborn committee of sneering, peasant-hating governors, there’s no second side of the argument about an aggressive foreign campaign to convert a sitting religion. Although one could argue that a certain character’s (trying to stay spoiler free here) bridging between the two cultures and the head-butting exchanges serve as the counterpoint.

Personally, I think Silence is a spectacular passion project (one which Scorsese has been trying to make for twenty plus years) and one that speaks bluntly about the difficulties of being a religious individual. What’s more its release is perfectly timed as waves of isolationism, mistrust and religious discord are at an all-time high. The more we step toward a truly global society, the more there will be people who want to resist it (for whatever reason) and at its most extreme resistance we have what happened to Japan in the 17th century, a complete shutting of all borders with no one arriving or leaving without extreme personal risk. As with all passion projects, the results will please a select group of people but as a thoughtful and patient piece of cinema, I think it’s a triumph.

Release Date:

3rd January 2017

The Scene To Look Out For:

In between the various scenes of torture are a handful of conversations and musings on the nature of God, religion and devotion. A particularly noteworthy exchange takes place between a fatigued Rodrigues and the inquisitor. To explain his feeling about foreign influence, Inoue recounts a story about a great lord who had four warring concubines and only found peace when he banished them all. He goes on to draw a parallel between the lord and the nation of Japan and the concubines being England, Holland, Spain and Portugal. Rodrigues counters with the notion of the lord adopting a single consort in the form of a wife whom he loves, only for Inoue to retort that by that example, Christianity is an ugly wife and it would not suit the lord at all. It’s a very plainly shot sequence but wonderfully enacted, giving a clear sense of two equally stubborn points of view. The real difference, that hadn’t been fully explored up until that point is how seemingly hopeless Rodrigues’ case is. Throughout the whole thing, the Portuguese priest is treated hospitably but it is merely a veneer. In actuality, he is little more than a prisoner of war and one who can be used to great advantage if he falls in line. Throughout the whole thing, Rodrigues is passionate, restless, tired and emphatic (partly due to the way he has been psychologically damaged by the torture) whereas Inoue maintains an air of calm and control throughout, always giving the impression that he has the upper hand. A prime example of a brilliant cast and crew firing on all cylinders without relying on flashy angles, cutting or gimmicks.

Notable Characters:

**Spoiler elements within**

The most interesting character, for his many flaws, questionable motivations and split loyalty is the vagabond, Kichijiro. The film offers so many questions to the internal workings of this man but it seems almost impossible to answer any of them with conviction. It’s hard to know if he genuinely renounces his own sins or if he simply plays each side to his own advantage. Once his backstory is revealed it clouds his motivations even more and serves to illustrate the burrowing power of religion, which seemingly reappears even when all trace is supposedly lost or suppressed. All of which is down to a fantastic script and an outstanding performance from Kubozuka.

Highlighted Quote:

“The hard thing is to die for the miserable and corrupt”

In A Few Words:

“Despite a few questionable missteps, Silence is a masterful film reminiscent of a style long since absent from contemporary releases”

Total Score: 4/5

![The Red Right Hand Movie Reviews [Matthew Stogdon]](https://reviews.theredrighthand.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/cropped-header1.png)