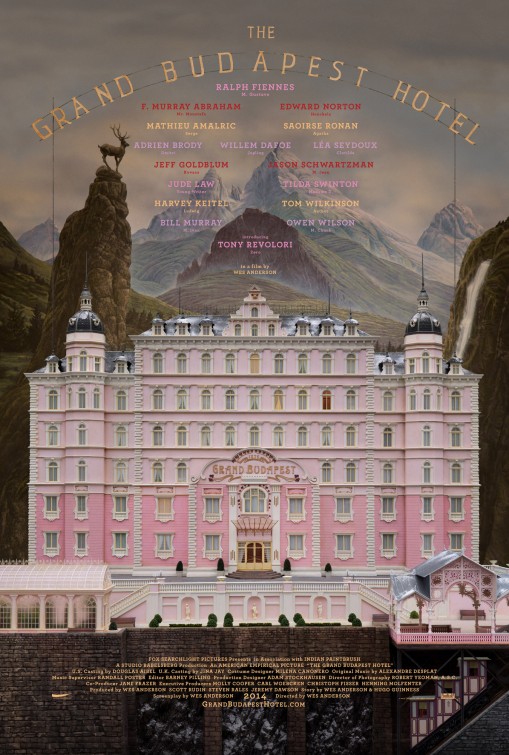

A Tale Of Love And Art

Director

Wes Anderson

Starring

Ralph Fiennes

Tony Revolori

Describing the aesthetic of a Wes Anderson film to someone who’s never seen one (or trying to defend it to someone who doesn’t care for it) is incredibly difficult. You find yourself using words like surreal, beautiful, shockingly touching at times, funny, innocent, naïve, etc, maybe even drawing a comparison to the whimsy of Georges Melies. But it’s not that Wes Anderson’s movies are set in a quirky alternate universe but the characters that populate them perceive their setting very differently from the average human being. This, I believe, is the key to Anderson’s signature style. And personally, if you don’t love, worship and adore every one of them, you’re dead inside… but that’s just my opinion.

At its heart, the story is about a writer conducting an informal interview with a very lonely looking guest in a very rundown looking hotel. As the man’s tale unfolds, we learn that he was once a lobby boy at that very hotel, some thirty five years earlier and would later inherit the entire place, along with a vast fortune. The lobby boy in question is an immigrant refugee by the name of Zero Moustafa [Revolori] who serves under the direct tutelage of the hotel’s eccentric concierge, Monsieur Gustave H [Fiennes]. In addition to Gustave’s excess of personality, he has a penchant for liaising with older woman (specifically, rich, insecure, blonde, older women). One in particular, Madame D leaves the hotel and subsequently dies of suspected murder. At the reading of her Last Will and Testament we learn that Madame D has left her most prized possession, a portrait of a young boy holding an apple, to Gustave. This starts a chain reaction of events that traverses all over Eastern Europe as World War II slowly begins to escalate and sees Gustave and his ever-faithful lobby boy evading psychopathic henchmen, the military, the police and prison guards. As the film progress, it becomes clear that her unscrupulous son, Dmitri [Adrien Brody] has murdered her to advance his inheritance and intends to frame Gustave for the crime.

As with every Wes Anderson flick, the pacing and production design are very unique and unforgiving. If you can’t handle intermittent title cards, choppy time jumps, novelty models and miniatures (that aren’t trying to be realistic but feel reminiscent of shadow puppetry), extreme close-up cut aways and sporadic font usage, then you’re going to effectively hate this movie. But if you’re willing to suspend disbelief, the film surreptitiously lures you in with pretty pictures and humorous performances before springing something utterly horrifying or delivering a resonating pathos without the audience being consciously aware that a pluck on their heart string is imminent. It’s a beautiful thing to be a part of and a real badge of honour for the skill that both cast and his crew exhibit. Anderson is a very visual director. The way scenes are lit, framed and arranged is akin to that of a painting and the camera is almost always stationary or shot at simple straight angles. But more than this, subtle methods are employed to immerse you in the story’s flow. Point in case, this film takes place in three flashbacks, each of which has been shot with a different aspect ratio for each time period. A fact which should be hideously jarring but somehow magically bleeds together without really being noticed. But at an even more surface level, the costume design is lavish and delightful, the hotel itself undergoes a major refit from its decadent thirties look, to its drab (and very orange) sixties design. The whole thing is a marvel. This is also the third time that Alexandre Desplat has scored an Anderson production and it’s hard to imagine anyone else taking over instead. The partnership is so perfect and his music really does reflect what’s going on visually; not just matching the timing of the events but really working in parallel with the depths of the images and performances – giving the audience both a sense of enjoyment, foreboding, dread and delight in one scene.

Something I enjoy greatly about ‘Anderson relationships’ is that the story’s partners and young lovers are played so very passionately, without clumsily traipsing into unnecessarily overt and nauseating territory. Often getting married young, intensely loving or hating each other, producing children they find unusual or eccentric but equally love or hate with the same passion. It’s just a delightfully comical melodrama that takes the simple nuances of daily familial and romantic interactions and emphasises the more ridiculous aspects. People wonder why so many actors work with (or want to work with) Anderson and I believe this to be the answer. Getting to portray such intense characters who emanate such staggering control, only to lose it in a delightfully comic and Woody Allen-esque manner, it’s something genuine actors crave. And no matter who is added to Anderson’s vast stable, they all immediately feel like they belong. Thus the acting is stellar. From the leading roles, to the smallest cameos, to the offbeat supports, everyone has a unique role that conforms to the overall feel of the collective ensemble performance. None more so than Fiennes elaborate concierge, rife with personality traits, a fondness for finery and an expansive vernacular. This performance is seconded only by the compressed passion and loyalty exhibited by the largely unknown novice Tony Revolori. Revolori, despite being incredibly young and unheard of by the masses, is a very gifted and talented individual and feels extremely at home in this fast-paced, quick-tongued environment.

Of course, the movie is far from perfect. Like all strong directors, sometimes one can be too present in one’s own film. The narrative is coherent enough but when you remove the twee elements, we’re left with a very simplistic and underwhelming story which ends very abruptly. What’s more, the film jumps back three times in flashback form: starting with a young girl at a grave, then back to the author of the book she’s reading (and the dude in the grave, incidentally), then a younger version of said author and finally back to Zero’s story. All well and good and all neatly done but as a framing device, there’s not a lot of resolution. We see how the older Zero finishes his story, leaving out vast strides of time which are admittedly irrelevant but then we don’t revisit the later elements. I appreciate it’s a moot point inserted for the novelty of it but that’s kinda my point. I forgive this of Anderson, as I forgive Scorsese for his shocking disregard for scene continuity but should I? Am I praising something that is inherently flawed (even in a minor way) because I admire the director’s work? But this is the limit of my complaints. Everything else is so wonderfully on form that if you were too travel back in time and inform me that Anderson’s next production was terrible, I would only be able to ask, “How? The man’s being true to himself artistically.. he can do no wrong.”

Release Date:

7th March 2014

The Scene To Look Out For:

**horribly blunt spoiler**

Tricky. For a film made up of exquisite little standalone treats, it’s taxing trying to select only one. One moment that stood out for me, in the way it was shot, cut and acted would be the demise of Willem Dafoe’s character – a psychotically determined henchman named J.G. Jopling. After a brilliantly filmed chase scene down a race piste, Gustave is clinging for dear life on the edge of a cliff. Jopling silently walks up starts stomping on the ice. Without losing his charming politeness, Gustave informs Jopling that he hates him more than anyone else in the whole world. As Jopling continues stomping, Gustave seems to accept death and starts to recite poetry. At the height of the scene, Zero appears and shoulder barges Jopling to his death. There’s something despicably brilliant about the whole thing that leaves you chuckling at something very serious but all the while reminded, it’s just a bit of silly fun.

Notable Characters:

Without a doubt, Ralph Fiennes is the centre attraction. Gone are his early 2000’s appearances as a weird rom-dram lead and following the close of the Harry Potter franchise, his presence is almost always guaranteed to be villainous. Thankfully, The Grand Budapest Hotel allows Fiennes to be so wonderfully silly. Immediately the works of Peter Sellers comes to mind, with a man who can commit himself so thoroughly to a particular role and deliver something different, inspired and entertaining. You can call up absolutely any of his character traits (the fondness for long-legged poetry, his particular brand of perfume, his effete nature, his strict moral and ethical code, his momentary lapse of etiquette with a crass outburst) and it would instantly bring you back to a specific scene which revelled in it beautifully.

Highlighted Quote:

“I want to press charges. This criminal has plagued my family for twenty years. He’s a ruthless adventurer and a con artist who preys on sick, old, mentally weak and feeble women like my mother… and he probably fucks them too”

In A Few Words:

“Fantastical, elaborate and glorious, The Grand Budapest Hotel is just another fine example of what can be achieved when a director carves out their own style without worry or concern for appealing to the dull masses”

Total Score: 5/5

![The Red Right Hand Movie Reviews [Matthew Stogdon]](https://reviews.theredrighthand.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/cropped-header1.png)