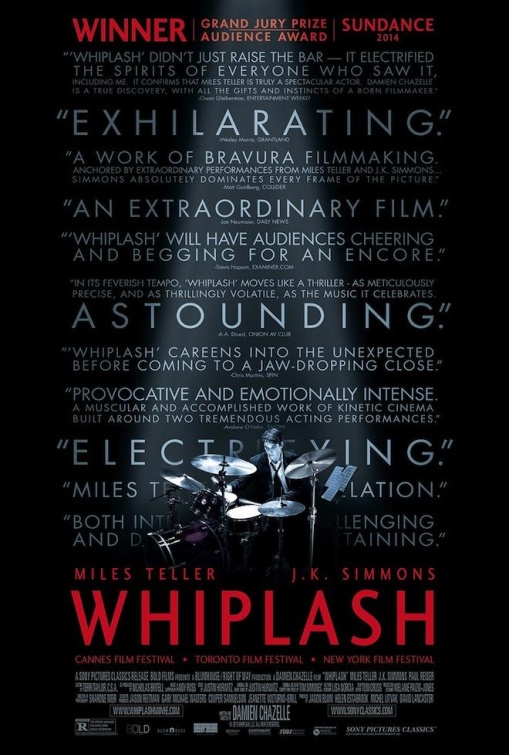

Not Everyone Has What It Takes To Be Great

Director

Damien Chazelle

Starring

Miles Teller

JK Simmons

Melissa Benoist

Paul Reiser

Set in the fictional Shaffer Conservatory music academy in New York, we are introduced to Andrew Neiman [Teller], a 19 year old drum student with a significant degree of talent. One night while rehearsing, Andrew is overheard by a ruthless teacher, Terence Fletcher [Simmons]. He demands Neiman play several styles for brief intervals, pauses and then leaves. A few days later Neiman is asked for another impromptu audition and manages to get into Fletcher’s personal band; an elite group of exceptionally gifted musicians. Before the first rehearsal, Fletcher takes Andrew to one side and calms his nerves by asking about him and his drumming. As the practice begins however, Fletcher immediately morphs into a terrifying and frankly monstrous tutor who belittles his students, emotionally batters them and physically assaults them. Despite his talk with Andrew, Fletcher hurls insults and abuse at the drummer demanding he play pitch perfect without error. As far as story goes, there’s not much to convey, Andrew increases his training and Fletcher remains unimpressed. They battle back-and-forth and any sort of life outside of the school is lost for Andrew. In all honesty, this brutal method of coaching has been seen many times before but rarely with this much intensity outside of sporting or war dramas.

There are several similarities between Whiplash and 2013’s Grand Piano, also written by Damien Chazelle. Both feature talented musicians who require the proper incentive to give an outstanding performance and both of their motivators are malicious torturers (to a degree). The difference really comes down to the direction and the performances. Grand Piano felt more like a mainstream thriller that a studio had warped and adapted into something they could market and sell. Whereas everything about Whiplash screams independent cinema; the cinematography, the direction, the editing, the almost invisible peripheral performances, the overwhelming emotional tension thrust upon the audience, in these areas, the film thrives.

As with most independent films, this feature is predominantly about character, more than the story, more than the music, character is paramount. Unfortunately, it only really has scope for two characters: Andrew and Terence. Anywhere else this could be a massively detrimental point but for a movie rooted so deeply in the nature of obsession, it makes perfect sense. And yet, I can’t help but feel the supporting roles were just as important but criminally neglected, specifically, the Nicole character, whose entire presence felt underdeveloped and unnecessary, and Andrew’s father Jim, who has two key moments throughout the film but is largely only wheeled out to give Andrew a nurturing coddling.. which is apparently the wrong kind of support. But even Andrew himself, with all his drive, devotion and energy is shadowed by Terence Fletcher. Not because he’s louder or more flamboyant but because he has more depth and charm (if that’s the right word). Andrew is focused with such blinkered vision that it makes his choices difficult to identify with, whereas the mystery and tyranny of Fletcher intrigue the audience. Subsequently, the film becomes more about him and his motivation. But to understand this character we need to question the nature of bullying and abuse. Does abuse for the sake of a ‘purpose’ constitute as passionate drive or just abuse? Are we to believe that because Fletcher is under the impression that his brow-beating method works, he is justified in his treatment of young people? Like a blacksmith taking a rod of iron and after continually immersing it in fire and beating it mercilessly, forges it into a sharply edged, perfectly crafted steel sword – but nothing of the original form remains (I appreciate that’s not entirely accurate but humour me). Fletcher isn’t honing musicians, he’s crafting living instruments. I’m not saying the film portrays this positively or encourages it, merely illustrates the journey to success that this musician underwent and that without the drums, his life was a vacuum.

Yet I’m still torn by the method. If an extroverted individual goes into a shop and is greeted by a friendly extrovert, they feel invited and their shopping experience is well received. Maybe they stay longer, maybe they buy more than they initially would and perhaps they walk away thinking fondly of the experience, pledging to return again. If, on the other hand, that very same extrovert greets an introverted customer, they could feel the entire shopping experience was unpleasant and leave before making a purchase or even browsing. This was touched upon in the notion that one of Fletcher’s former protégés, who had achieved great success, suffered from immense anxiety and killed himself. This is a clear example that Fletcher’s abuse didn’t work, even when it seemingly did. But the movie bats this away with the reaffirmation that if you fail at any point, you were never destined to succeed in the first place. Now, I don’t believe this observation is necessarily a fault of the film and I wouldn’t mark the film down for this development, primarily because the characters delivering the dialogue are in themselves contorted and biased narrators.. but it’s still an uncomfortable message. As I left the cinema, I couldn’t help but wonder if this film ended incorrectly. Arguably it ended the only way it could and elicited the perfect emotional response from the audience but from a personal perspective, it was far too upbeat. Music is an obsessive artistic pursuit unlike most any other and this film purports that practice makes perfect but that simply isn’t the case. If anything, that goes against the very nature of what Jazz is, which I believe to be the spontaneous and fluid movement of music, not the exact repetition and rehearsal of set composition. It felt almost as if someone remade Full Metal Jacket and after the first half decided that R. Lee Ermey’s motivation of Vincent D’Onofrio’s character would inspire the young man and he goes on to win the fucking Vietnam war. To my mind that kind of artistic drive can only end one way: death. As such, films like The Red Shoes, Black Swan and Control are superior because they act as a warning. That kind of devotion, commitment and exertion comes at a price. Maybe I’m wrong, maybe Whiplash tries to tell us something different, maybe the message is that the music and the performance are eternal, the musician is merely the honed instrument, the catalyst. But as a human, shouldn’t there be something more? To my mind, the movie responds, what more do you want? And with that, every flaw and fault of the film seemingly melts away.

Release Date:

16th January 2015

The Scene To Look Out For:

This movie is less an unfolding story and more a sequence of beautiful shots and memorable interactions. There are plenty of standout moments and visuals that both crush and elevate the audience. If anything in particular stood out to me, it was something that felt so curiously out of place. Andrew has only just started with the band and acts as the core drummer’s reserve (essentially, he tunes the drums and turns the pages). The core drummer walks off stage and hands the playbook to Andrew to look after. In order to purchase a drink from a vending machine, Andrew places the folder on a chair behind him and enjoys his drink. A few seconds later the core drummer returns and demands his playbook, which is now mysteriously gone. There. Right there. That’s my problem. At the start of the scene, Fletcher specifically says if he sees a playbook simply lying around there will be hell to pay. So, you know someone is going to lose their book. But there’s no logical explanation as to what happened to the book, it’s just gone and the idea that Fletcher saw it and took it is beyond far-fetched considering the length of the corridor and the amount of time it was unguarded. It’s just a bit cheap. And with brilliant direction and amazing performances, this kind of sloppiness stands out like a sore thumb.

Notable Characters:

As stated earlier, there really only are two performances in this film and depending on the kind of person you are, you’ll either see Miles Teller or J.K. Simmons as the dominant presence. Some will say that the energy levels are equal in both but the ferocity in Simmons’ performance is more captivating, others will say that Teller’s robotic one-track obsession is more spellbinding, especially when you consider he’s actually playing the instrument. Personally, it comes down to the Amadeus argument for me. I can’t choose which of the two is more important or impressive because without one, you wouldn’t have the other. And as far as acting is concerned, both deliver career highs that will no doubt garner them unmitigated levels of praise.

Highlighted Quote:

“Either you’re deliberately out of tune and sabotaging my band, or you don’t know you’re out of tune and that’s even worse”

In A Few Words:

“A very powerful and gripping exploration of obsession and dedication with clearly impressive performances but left an unpleasant aftertaste that didn’t sit right with me”

Total Score: 4/5

![The Red Right Hand Movie Reviews [Matthew Stogdon]](https://reviews.theredrighthand.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/cropped-header1.png)