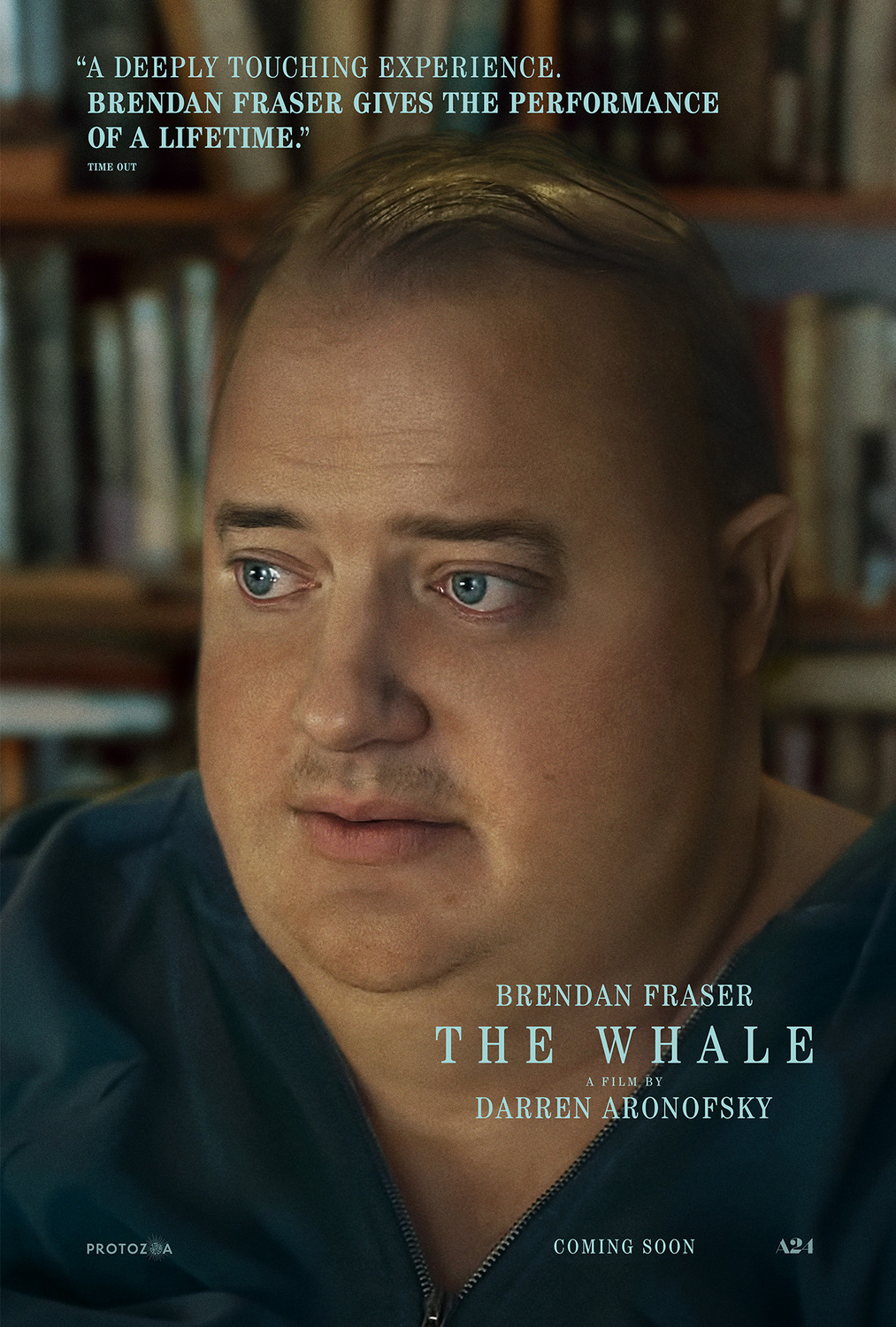

Director

Darren Aronofsky

Starring

Brendan Fraser

Hong Chau

Ty Simpkins

Sadie Sink

Following the death of his partner, Charlie [Fraser] puts on weight to the extent that he has become morbidly obese. With extremely limited mobility, Charlie becomes reclusive and teaches writing courses online, keeping the webcam off to hide his appearance. Charlie’s only three frequent visitors are Liz [Chau], a nurse and seemingly his only friend, an enthusiastic young missionary named Thomas [Simpkins] and Charlie’s estranged teenage daughter Ellie [Sink]. Charlie refuses all manner of medical aid, citing insurance costs, and seems to have largely accepted that he will likely die of congestive heart failure within the week. But before that time lapses, he wants to reconnect with his daughter, if only for a limited time.

The Whale is undeniably a performance-led piece, and traditionally, this comes with certain peaks and troughs. Specifically, the central character is usually a fascinating exploration that draws you in, while other supporting elements feel peripheral and undercooked. What makes this an unusual turn of events, is that Darren Aronofsky is directing. And, as a man known for his intense, in-your-face style, this feature hits a little differently; in a way that isn’t too dissimilar from The Wrestler. A calmer, more reserved piece with a play-like structure – which I wrote in my notes before realising that it The Whale in fact an adaptation of a play of the same name. And while Aronofsky could have injected his patented signature, it would likely have detracted from the movie’s prime focus. What’s more, without the constant sense of dread (take something like Mother! for example) the pacing would have been more pronounced. As it currently stands, the two hour runtime flies by.

The choice by long-time collaborator Matthew Libatique to shoot the film with dim lighting may lead some to believe it’s quite muddy and grim. But in fact, the cinematography is so rich that it takes what would be a mundane setting and gives it an almost Dutch Golden Age depth and richness. Additionally, shooting in a boxy 4:3 frame means Charlie literally fills the screen and makes his apartment (the film’s sole location) feel even more claustrophobic. Working in harmony, the score is equally fantastic, with deep tragic tones and a building ominousness, indicating the worst will inevitably happen. Composer Rob Simonsen also injects plenty of intentional nautical themes: from the naming of individual tracks, to the evocation of fog horns in the night. Or, for a specific example, when Charlie is cross-referencing his BPM results online and being horrified by what he finds, the music rises and falls, like waves lapping at the shore. Which, as the story unfolds, is in fact a core memory and important motif.

Now, it’s important to note that a story about someone literally eating themselves to death is an incredibly loaded subject. It invites all manner of scrutiny and criticism for how the central character is portrayed. Primarily as it would be so easy to simply view this as an exercise in pity and disgust. But rather than an ogling of grotesquery, The Whale illustrates the human tragedy of a man at the end of his life and the obsession that brought him there. From the psychological triggering of his late partner neglecting himself and wasting away, to his stubborn refusal to pay for help because any funds he has are intended for his daughter’s future. Yes, this is a man who is a man who has been brought low and when he gorges himself (during his deepest self loathing) the events are framed like a horror. But Fraser brings such a whimsy, charm and beauty to the role, and carries himself through painfully beautiful prosthetics in a way that doesn’t feel tawdry or disrespectful.

Furthermore, films do not exist in a vacuum. In years to come people may watch this film and remark on Fraser’s dedication to the role. But to watch it without appreciating all that man has been through in recent years (emotionally and physically), is to miss some of the nuance and earnestness that makes Charlie such a captivating and tragic figure, who never abandons his sense of optimism and hope.

This feature isn’t without its flaws though. It’s simplistic in its investment in the promise of others, and is delivered with the utmost, teary-eyed sincerity, that could come off as incredibly trite or over-sentimental for some. But for every stumble, it is – to bring us back to an early comment – a fascinating exploration, which draws you in and holds you.

Release Date:

03 February 2023

The Scene To Look Out For:

Charlie has such faith in others but his existence is one that limits his ability to enjoy it. To explain through example, the former English professor asks his daughter to write something, anything, as long as it’s honest. And all she offers are three small sentences. Initially dejected, Charlie reads over them again and realises her scathing comments are actually a haiku. With this, he begins to laugh but the joy at reading his daughter’s defiant poem, causes him to enter a coughing fit and presents another thundering reminder how close he is to death.

Notable Characters:

There are only a handful of other acting parts but Sadie Sink stands tall. Ellie is such a wonderfully abrasive, troubled kid. The sheer embodiment of teenage rage, the shell of which is slowly ebbed away before lashing back in the most brutal ways. It’s a difficult performance to get right and one that the audience, having spent time with Charlie, will push back against. But she serves as a reminder that Charlie isn’t a saint. He may not deserve Ellie’s sharpest of barbs but he’s also not a thing to be saved, or pitied, or spared for his actions. And to bring that level of skill, at that age, is incredibly impressive.

Highlighted Quote:

“Ellie, look at me. Who would want me to be part of their life?”

In A Few Words:

“Lacking in certain lasting narrative qualities but, for the main performance alone, The Whale beautiful.”

Total Score: 4/5

![The Red Right Hand Movie Reviews [Matthew Stogdon]](https://reviews.theredrighthand.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/cropped-header1.png)